Black History Spotlight: Flatbush Connections

February 8, 2023

As we celebrate Black History Month, Prospect Park Alliance is engaging the public around ReImagine Lefferts, an initiative to re-envision the mission and programming of the Lefferts Historic House museum to further focus on the stories of the Indigenous people of Lenapehoking whose unceded ancestral lands the park and house rest upon and the Africans who were enslaved by the Lefferts family. The initiative recently received a prestigious Humanities in Place grant from the Mellon Foundation.

On Saturday, February 11, Prospect Park Alliance is hosting a ReImagine Lefferts Community Conversation to share ongoing research and seek public guidance and feedback to inform our planning. To date, we have identified 25 people enslaved by the Lefferts family at the house between 1776 and 1827, including a man named Isaac.

This research would not have been possible without the support of civic leaders in Flatbush and beyond, such as Shanna Sabio, co-founder of GrowHouse Community Design + Development Group and trustee of the Flatbush African Burial Ground Coalition, a Black-led, multiracial coalition that works to preserve the Flatbush African Burial Ground from further desecration. Sabio developed a walking tour of Flatbush that explores Isaac’s story. Sabio shared her insight on the many connections between Prospect Park Alliance’s ReImagine Lefferts Initiative and the Flatbush African Burial Ground Coalition’s ongoing dedication to sharing the stories of the resistance and resilience of those enslaved in Brooklyn.

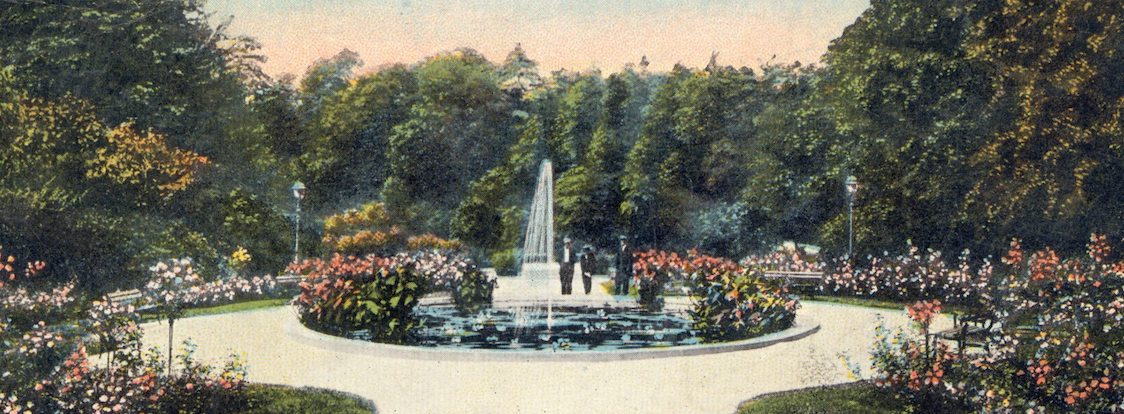

A 1905 postcard of the Lefferts Historic House in its original location on Flatbush Avenue before it was moved to Prospect Park in 1918. Photo courtesy of Prospect Park Archives/Bob Levine Collection.

“It’s fairly likely that people who were enslaved at the Lefferts Homestead also interred their loved ones at the Flatbush African Burial Ground,” shares Sabio. “Just as the Lefferts House is undergoing a revitalization and will become a site where people can learn about the complex and often painful history of Brooklyn, the Flatbush African Burial Ground should be a site of pilgrimage and remembrance.”

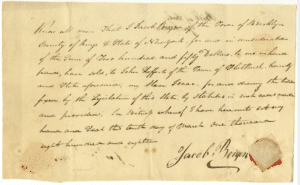

Isaac was sold by Jacob Bergen in Red Hook to John Lefferts for $250 in March of 1818. The high price suggests that Issac was extremely skilled and that Lefferts may have purchased Isaac to run his 250-acre farm in Flatbush. However, less than three months after his purchase, Isaac escaped enslavement along with his wife Betsey and her three sons Harry, Stephen, and Joshua, who were enslaved by the Martense family across the street from the Lefferts’ farm.

The Bill of Isaac’s Sale for $250 as documented between Jacob Bergen and John Lefferts.

[Isaac] Bill of Sale, Jacob Bergen and John Lefferts, March 10, 1818; Lefferts Family papers, ARC.145, Box 1, Folder 9; Brooklyn Public Library, Center for Brooklyn History.

Both ReImagine Lefferts and the Flatbush African Burial Ground Coalition seek to engage the public in a thoughtful dialogue about the legacy of enslavement and exploitation. On the necessity to share the stories of those enslaved on this land, Sabio says “Isaac’s story is a great example of the ways that enslaved people resisted their oppression. His labor, along with the labor of all those enslaved at the Lefferts House and throughout Flatbush, helped to cement the power and influence of their enslavers, and yet their stories are generally left untold. Unearthing, preserving, and sharing these important histories helps make sure that we learn the lessons of the past so we’re not doomed to keep repeating the same mistakes.”

The Flatbush African Burial Ground Coalition’s walking tours delve further into Isaac’s story and its profound significance. Learn more about the historic connections between the burial ground and the Flatbush community at the Coalition’s upcoming Community Day of Action and Remembrance on Saturday, February 25. Attendees will clean up the perimeter of the burial ground and have the chance to join the first walking tour of the year to learn more about the lives and stories of those enslaved in the area.